Mapping Non-European Visions of the World

Maps drawn by Indigenous artists at the behest of the Spanish in the 16th century illustrate the amalgamation of visual traditions during the early years of contact between Indigenous groups and colonizers.

AUSTIN, Texas — In February of 1519, Hernando Cortés and a group of Spanish conquistadores sailed 11 small caravels from Punta de San Antón in Cuba. Two months later, they landed in what is today Cancun, Mexico. By August, Cortés and his expedition began their journey inland; two years after that, the Mexica capital Tenochtitlán (now Mexico City) fell to an army made up of Spanish as well as Indigenous peoples from other cities. The fall of Tenochtitlán, in addition to epidemics of European-introduced diseases, would begin the long process of Spanish colonization that history has alternately called conquest or genocide.

At the same time that Spain began exploring (and “discovering”) the inhabited Americas, European cartographers focused on creating maps with ever-increasing geometrical precision and then reproducing those maps via engravings and woodcuts. But Europeans were not the only people to create representations of geographies and map spaces the of the Americas — and their mathematically based cartography was not the only way 16th-century landscapes were recorded.

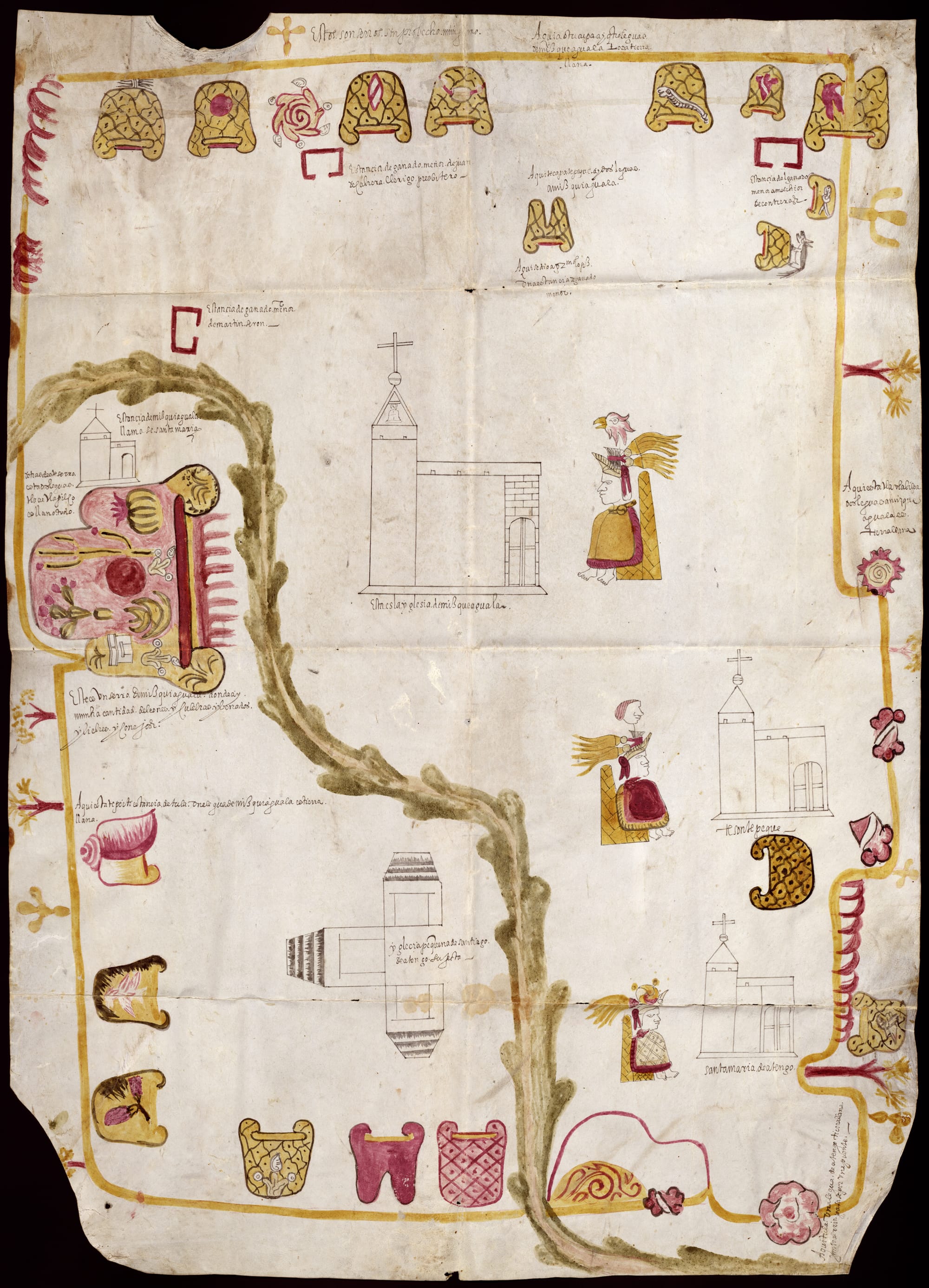

Mapping Memory: Space and History in 16th-Century Mexico — currently on view at the Blanton Museum of Art in Austin, Texas — features 19 maps drawn by Indigenous artists at the behest of the Spanish between 1579 and 1581. These maps illustrate the amalgamation of visual traditions during the early years of contact between Indigenous groups and colonizers.

The maps were created in response to a questionnaire sent throughout New Spain in 1577 by the Office of the Cronista Mayor-Cosmógrafo. Following a decree by King Philip II, the office was to formally describe Spain’s colonial holdings. It authored, printed, and distributed a 50-item questionnaire to local officials in the Viceroyalties of New Spain and Peru to gather information about the landscape and peoples. The questionnaires were returned between 1579 and 1585 and several of them were accompanied by maps made by Indigenous artists as illustrations. The responses became known as relaciones geográficas.

Mapping Memory shows 20 of these relaciones geográficas from the Benson Collection. There were 191 responses to the questionnaire; 43 are in the Benson Collection and more than half of those were accompanied by one or more maps, known as pinturas. Those currently on exhibit record traditions of mapmaking that demonstrate alternative uses of space to Europe’s geometry and cartographic projection. Rather, the pinturas, drawn by unrecorded Indigenous artists, show a stage created of and for human action.

“What the maps best show us is the Indigenous world — how its inhabitants, still reeling, no doubt, from the blows of conquest, reshaped their once insular maps to keep pace with the rapid changes in their understanding of the surrounding world,” historian Barbara Mundy, who is not affiliated with the exhibition, offers in The Mapping of New Spain: Indigenous Cartography and the Maps of the Relaciones Geográficas.

Most were created with watercolors and ink on paper, although one artist illustrating Atengo and Misquiahuala used tempera on deerskin. The style of each is unique, as are the colors and brushwork; the majority measure approximately 16 to 24 inches by 24 to 36 inches, in both landscape and portrait compositions. Some of the pinturas, however, are massive — the watercolor and ink map of the Mixtec community of Teozacoalco (in present-day Oaxaca), for example, is more than twice the size of the others.

In addition to mapping the town’s boundaries, the Teozacoalco pintura records the name of the town as chiyo ca’nu, in the local Mixtec language name instead of the most widespread Nahuatl, from which Teozacoalco derives. It describes 46 logographic place-names, and 10 generations of local rulers. Smaller towns in Teozacoalco’s sphere of influence are shown connected by a network of rivers and roads. This pintura, unlike the more compact ones, has clearly been folded, unfolded, and refolded over time. Dark smudges along the map’s creases underscore that the map was a circulating object, part of Spain’s empire-building, as it would have gone with the relacion geográfica back to Spain.

In addition to the pinturas, Mapping Memory showcases 16th-century printings of Cortés’s letters to Spain’s King Charles V justifying his expedition and characterizing the ensuing Spanish-Mexica war as an absolute conquest for Spain. Also on display is Charles V’s 1529 decree appointing Cortés as Captain General of New Spain. These supplemental items — the decades of letters, decrees, and even the European-made maps of the Americas prior to King Philip II’s formal questionnaire — create a very clear sense that Spain’s empire was formed just as much through print, maps, language, and institutions as through military expeditions.

Mapping Memory offers an incredibly nuanced portrait of the material legacy of empire and reminds audiences that Indigenous visual traditions of mapmaking persevered through the decades following Spanish contact.

Mapping Memory: Space and History in 16th-Century Mexico continues at the Blanton Museum of Art (200 E. Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd. Austin, Texas) through August 25. The exhibition was curated by Rosario Granados, the Marilynn Thoma Associate Curator, Art of the Spanish Americas at the Blanton Museum of Art.

Corrections: This piece has been updated to clarify that Mapping Memory showcases 19 maps, not 20, and also to clarify the name of the town chiyo ca’nu, in the local Mixtec language.